From Fragile to Faultless: Kubernetes Self-Healing In Practice

Overcoming imperfections of managed Kubernetes with early self-healing.

Written by Grzegorz Głąb and Nibir Bora, members of the engineering teams that work on core infrastructure.

Many organizations opt for managed Kubernetes distributions like Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS) to get up and running quickly without needing a large engineering team to operate Kubernetes clusters. This is a core design principle of the Core Infrastructure team at City Storage Systems. However, over the years, we’ve learned that the true operating cost of managed Kubernetes distributions is not in fact zero.

Even public cloud experiences occasional failures. Hardware faults, kernel misconfigurations, network bottlenecks, problematic rollouts, resource scarcity, security vulnerability, etc. leads to complications lasting for minutes, or in some cases, weeks. In this blog we share our experience illustrating how minor glitches, if left unattended, could quickly escalate and impact business continuity.

Rather than engaging in constant firefighting we designed a self-healing framework, often implementing automations with a turnaround time of as little as 1 day. These automations were sometimes temporary fixes until resolved by the cloud provider, and at other times, they became permanent enhancements to our platform’s reliability. While our journey began with a focus on AKS, this framework is a general-purpose pattern to improve resilience of any Kubernetes platform.

The Self-Healing Framework

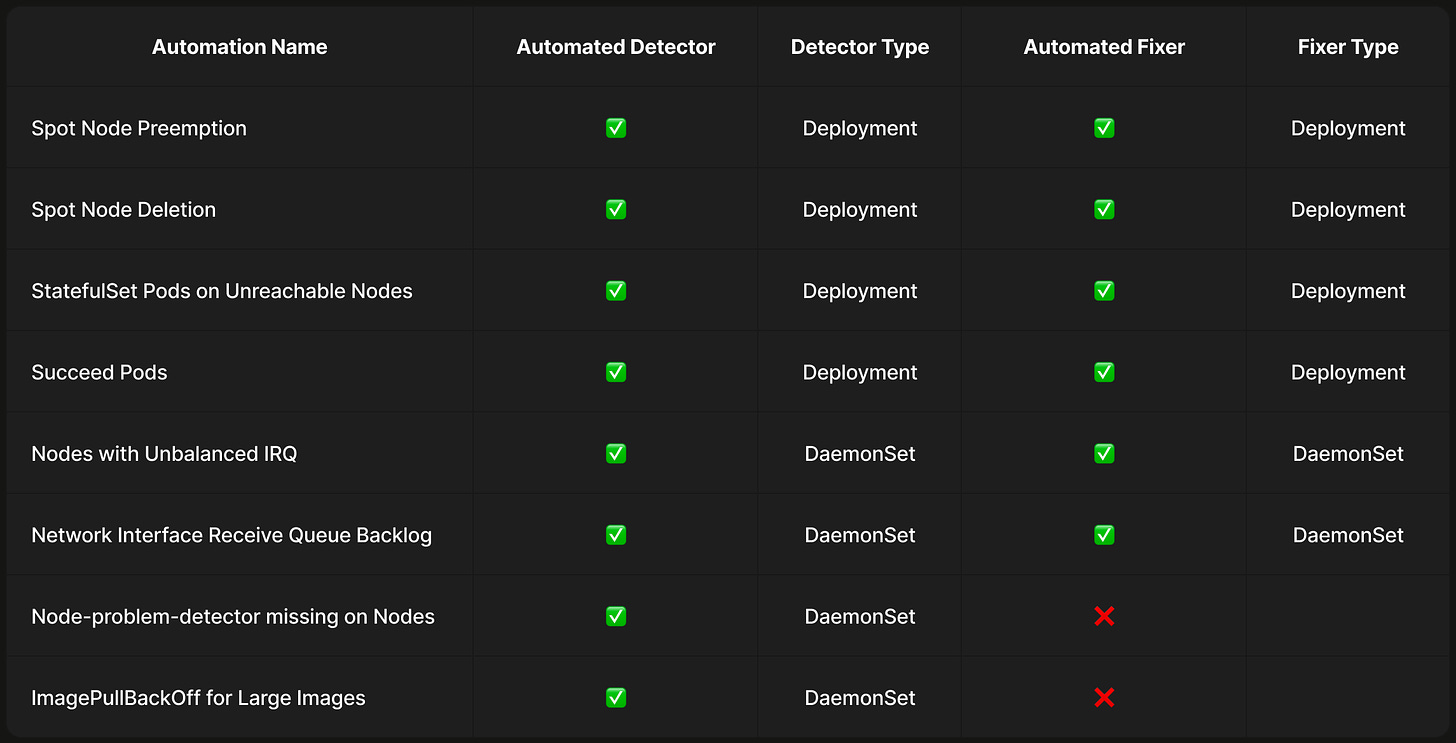

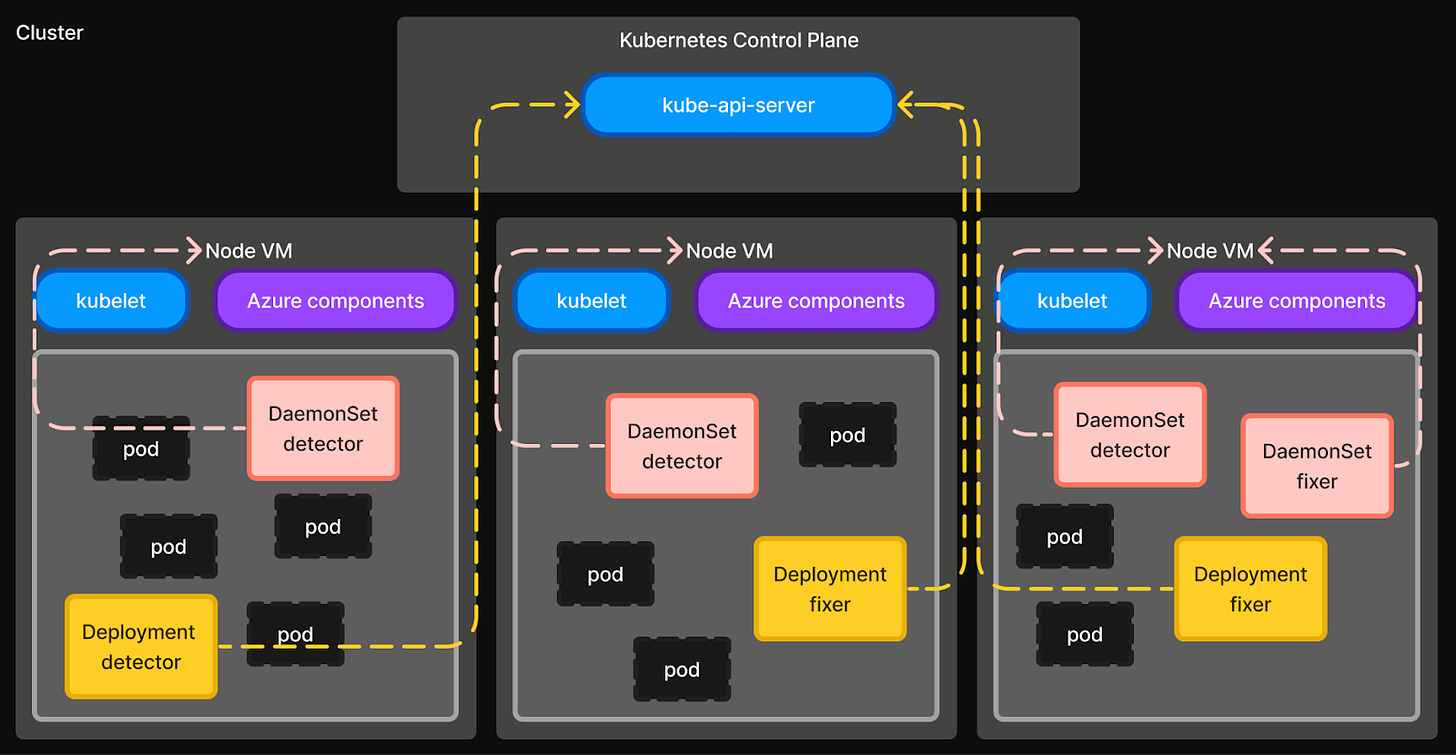

The first self-healing use case was implemented as a monolithic program. But, as we added new use cases, we identified several reusable libraries that nudged us to organize it into a framework. The framework today consists of Automations that each address a specific failure mode. Automations are implemented as an independent Detector and a Fixer, which are either a controller or a Go program.

Detectors are responsible for collecting signals and flagging failure conditions. There are two types of detectors - Cluster level (Deployment) and Node level (DaemonSet). Cluster level detectors monitor for cluster-wide failure events and have permissions to watch or create API server resources. Node level detectors monitor for node level failures (e.g. misconfigured OS flags, image pull issues, missing systemd services, etc.) and have privileged host access.

Fixers complement detectors by executing remediation steps to rectify or cleanup failure states. Similar to Detectors, there are two types of fixers - Cluster level (Deployment) and Node level (DaemonSet). Cluster level fixers execute remediation actions that operate on cluster-level resources and have permissions to watch API server resources. Node level fixers execute remediation action at node level, or operations that require privileged host access.

Generalizing as such allows us to keep the framework simple and appropriately isolate permissions. This was key to swiftly adding new automations when needed. Whenever we identify a new degradation, we implement and deploy the corresponding detector and fixer across all our clusters. The following automations are a few examples that shielded our internal developers and applications from potential impact, and also significantly reduced our team’s support toil - cutting it in half from 30% of engineering time.

Building these automations over the last year and a half has taught us some key lessons:

Kubernetes is not the end product. It is a framework for building platforms. Managed Kubernetes still greatly benefits from business specific customizations that create leverage for developers.

Abstractions don’t erase underlying layers. Kubernetes, while powerful, still requires us to dive into the host VM or kernel layer for deep debugging - a skill set we've honed through experience.

Cost optimization has a reliability tax. Optimizing cost needs to be counterbalanced with increased vigilance on reliability. For example, running stateful workloads on Spot nodes required us to invest further in automation.

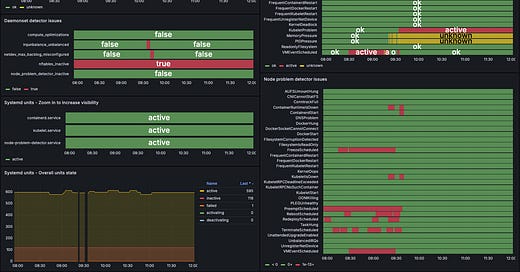

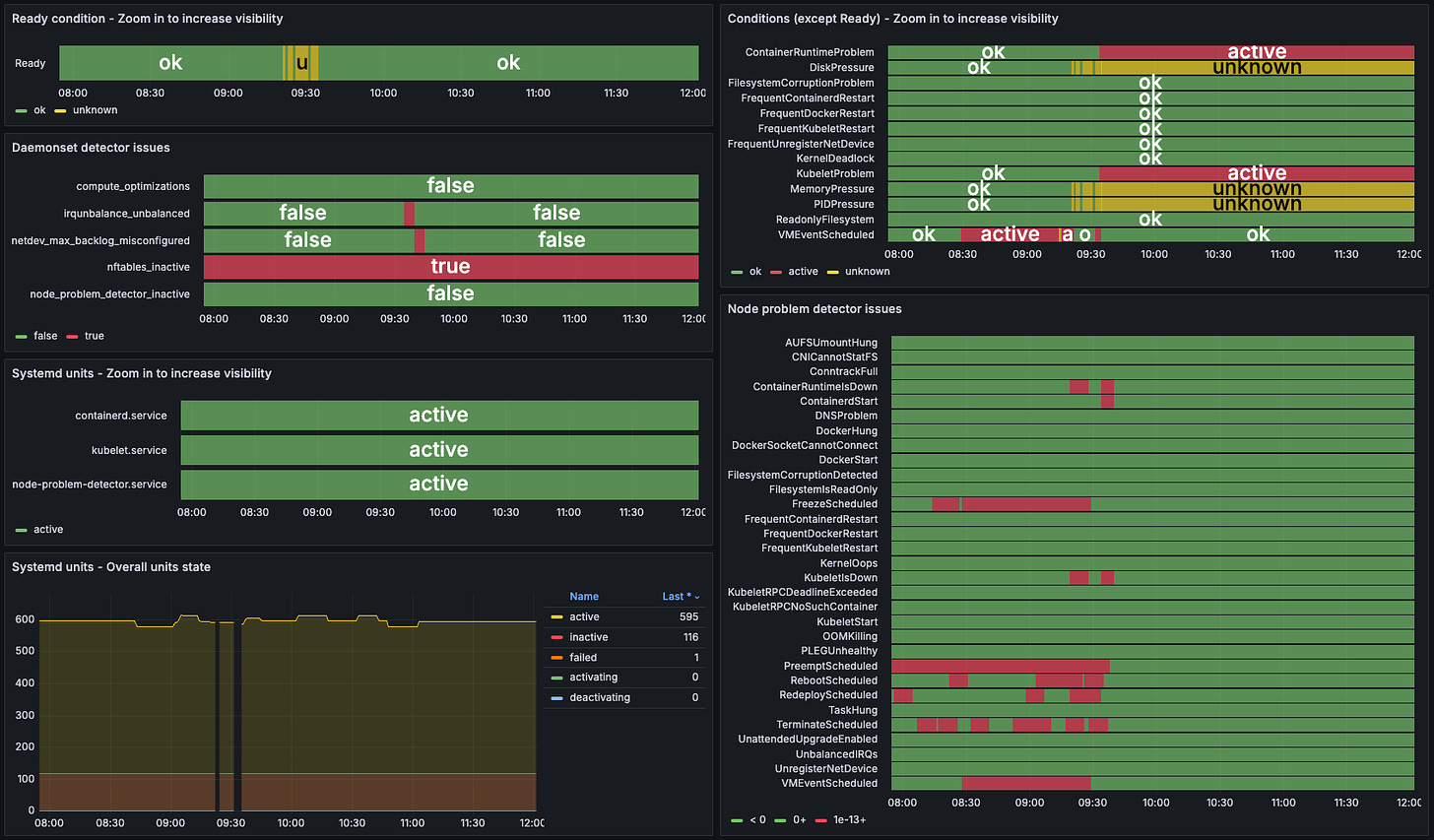

Cloud bugs cannot be predicted. Instead of anticipating imaginary failure scenarios, it’s better to optimize for speed of diagnosing unforeseen issues and implementing automation for them. For example, we consolidated all node malfunction signals on a single “node inspector” dashboard empowering our developers to respond swiftly when paged.

In the following sections we describe a few of the automations in detail, covering how each failure mode was identified and how we automated its self-healing.

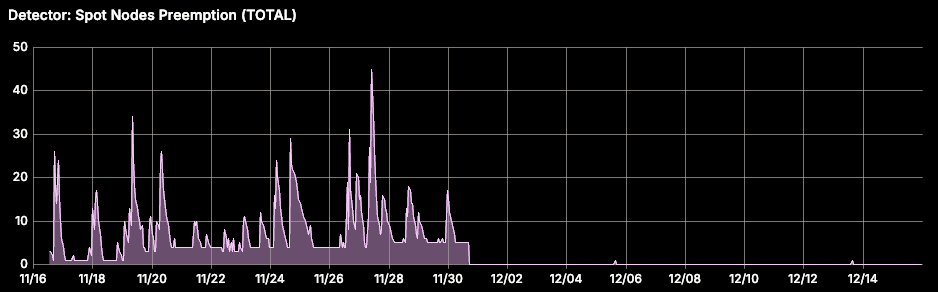

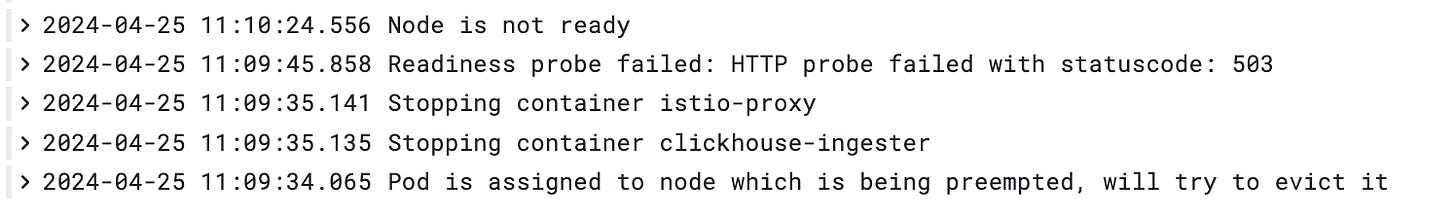

Handling Abrupt Spot Node Preemptions

We use Spot nodes extensively on our Kubernetes platform to optimize resource costs, running both stateless and less critical stateful workloads. However, Spot nodes on AKS lack any SLA, which can lead to potential abrupt preemptions. We experienced an incident where a large number of Spot node preemptions caused multiple stateful workloads to fail, causing cascading application failures resulting in downtime.

When Spot nodes on AKS are preempted, a scheduled preemption event is emitted 30 seconds before the underlying VM is abruptly removed. The node isn’t cordoned, workloads aren’t gracefully shut down, and the Node isn’t deregistered from the Kubernetes API server. The Node object remains without a physical VM (see issue #3528) until cleaned up after 5 minutes due to failed heartbeats. When this happens, stateless workload pods (controlled by Deployment and ReplicaSet) are automatically rescheduled, but not StatefulSet pods. StatefulSet pods leave behind “phantom” pod objects (with .status.phase: Unknown) in the API server, which is not an acceptable behavior for our stateful workloads.

To address this, we implemented a self-healing automation that intercepts Spot node preemption signals and gracefully evicts all pods on the affected node. A detector watches for VMEventScheduled node conditions (example below) and creates a SpotNodePreemption Custom Resource (CR) with details for the fixer. The fixer then evicts the pods with a 10-second grace period.

.status.conditions: [

{

status: "True",

type: "VMEventScheduled",

reason: "VMEventScheduled",

message: "Preempt Scheduled : Tue, 14 May 2024 12:57:00 GMT",

lastHeartbeatTime: "2024-05-14T12:56:43Z",

lastTransitionTime: "2024-05-14T12:56:42Z"

}

]

Once this automation was operationalized, we noticed that some Spot nodes were still terminated without a scheduled preemption event. This was because when Node Problem Detector (NPD) queries Azure Metadata Service for the VMEventSchedule event, the request occasionally fails resulting in a NoVMEventScheduled node condition (example below). To handle this, we added another self-healing automation to clean up after terminated Spot nodes when the preemption event wasn’t intercepted. The detector creates a SpotNodeDeletion CR when a Spot Node object is deleted from the API server, and the fixer force deletes all pod objects on that node assuming they are no longer reachable.

.status.conditions: [

{

...

type: "Unknown",

reason: "NoVMEventScheduled",

message: “Timeout when running plugin \"/etc/node-problem-detector.d/plugin/check_scheduledevent_consolidated.sh\": state - signal: killed. output - \"\"”

}

]Handling StatefulSet pods on Unreachable Nodes

AKS node pools are built on Azure Virtual Machine Scale Sets (VMSS) infrastructure. We observed that VM failures in the VMSS layer often make AKS Nodes unreachable. When this happens, the node controller adds a NoExecute taint, and all pods on the node are evicted after 5 minutes. While stateless pods are rescheduled automatically, StatefulSet pods are not (see issue #54368, and design proposal). This can lead to data loss caused by under-replication in stateful workloads like CockroachDB or OpenSearch.

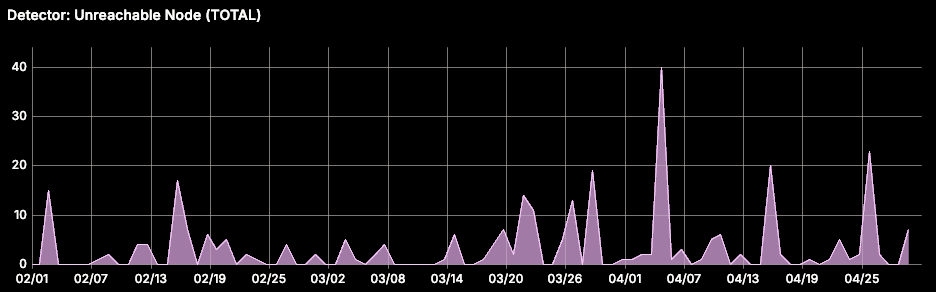

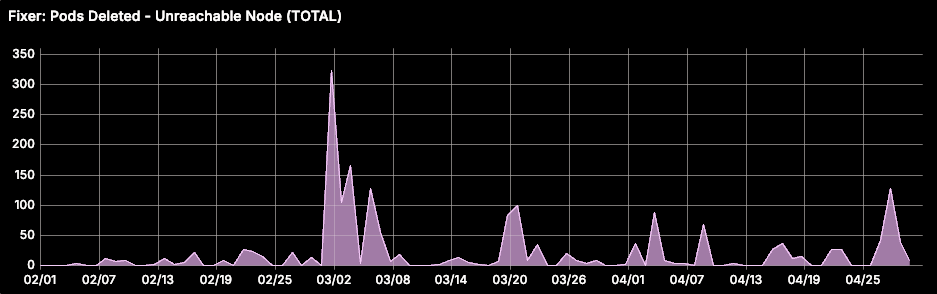

To address this, we implemented a self-healing automation that watches the Kubernetes API server for Node objects with a node.kubernetes.io/unreachable taint. The detector filters nodes tainted for more than 5 minutes, and the fixer force deletes all pods (assuming they are unrecoverable) on these nodes, allowing new pods to be scheduled.

Cleaning Up Succeeded and Evicted Pods

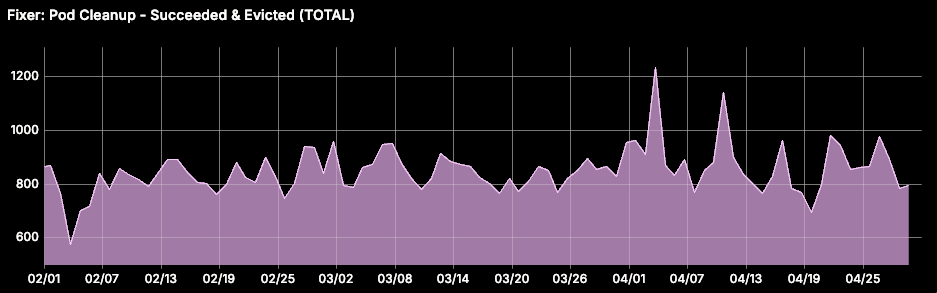

While investigating a cluster health degradation due to increased etcd disk size, we identified the accumulation of Succeeded pods as a significant factor. These were created by short lived cron jobs, pods without a controller (e.g. Flink jobs), and evicted pods. Since kube-controller-manager doesn't automatically clean up succeeded pods, this is a problem on our large multi-tenant clusters. This default behavior can be modified by configuring the --terminated-pod-gc-threshold flag. However, since we use managed Kubernetes the control plane is managed by the cloud provider and not user-configurable.

To address this, we implemented a self-healing automation that monitors the Kubernetes API server for pods with, either status.phase = Succeeded, or status.phase = Failed with pod.Status.Reason = Evicted. The detector flags pods that have remained in these phases for at least 15 minutes. This threshold is configurable per namespace. The corresponding fixer deletes these flagged pods from the API server.

Handling Network Packet Drops Due to Unbalanced IRQ

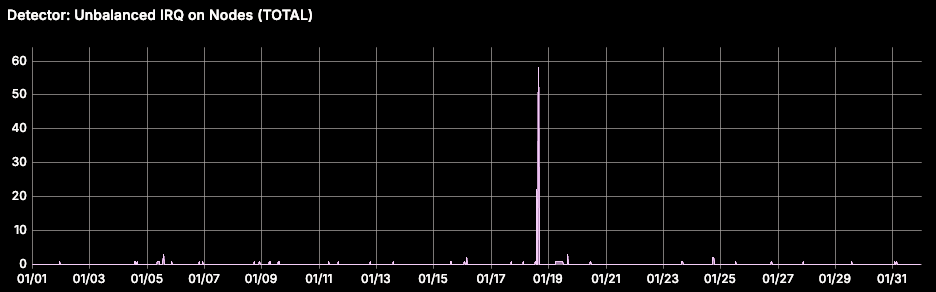

We noticed increased packet drop rates in network IO-intensive workloads, initially thought to be application errors. However, we saw that the nodes with affected workloads had VMFreezeEvents (see AKS docs). Investigation showed hardware interrupts from the node’s network interface were unevenly handled by only 2 of 8 CPU cores, causing 100% utilization on those cores (see detailed investigation in blog). Restarting the irqbalance service, which should distribute interrupts evenly, resolved the issue.

To address this, we implemented a self-healing automation that flags nodes where fewer than half of the CPU cores are configured to handle interrupts from the network interface. This is done by checking /proc/irq/IRQ#/smp_affinity, which denotes CPU core affinity to the interrupt request queue (IRQ). The corresponding fixer restarts the irqbalance systemd service on the host VM. We also expose the number of cores used for IRQ per node as a metric for continued observability. The upstream issue was later fixed in later versions of ubuntu (see bug #2038573).

Despite this fix, some packet drops persisted. This was traced to a backlog in the network interface's receive queue. We found if the receive queue size was set to less than 10000 it caused packet drops. To address this, we implemented another automation that flags nodes where net.core.netdev_max_backlog is less than 10000. The corresponding fixer, resets it to 10000 on the host VM.

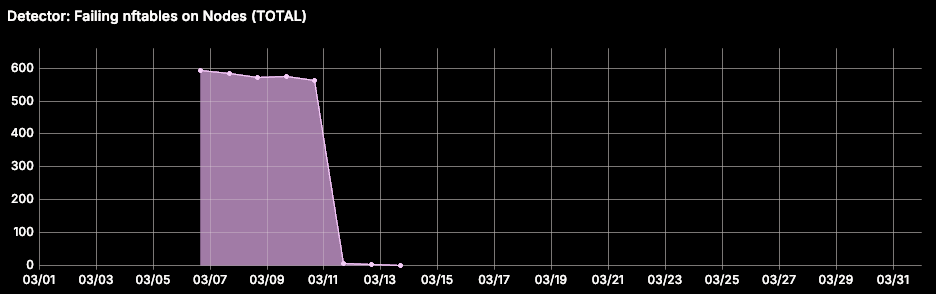

Addressing Failing nftables During OS Image Migration

While migrating our nodes from Ubuntu to Azure Linux OS, we noticed nftables wasn’t running on the migrated nodes. Kubernetes relies on nftables on the host VM for inter-pod routing rules on the node and egress traffic. This prevented Network Policies from being applied correctly, leading to irregular network failure on nodes. After investigation, we identified this was due to a missing newline in the nftables.conf file (see issues #4144 and #7301, and pull request #8310).

To address this, we implemented a self-healing automation that flags nodes where the host VM isn’t running nftables. The corresponding fixer corrects the nftables.conf file by appending a newline to the end and restarts the nftables systemd service.

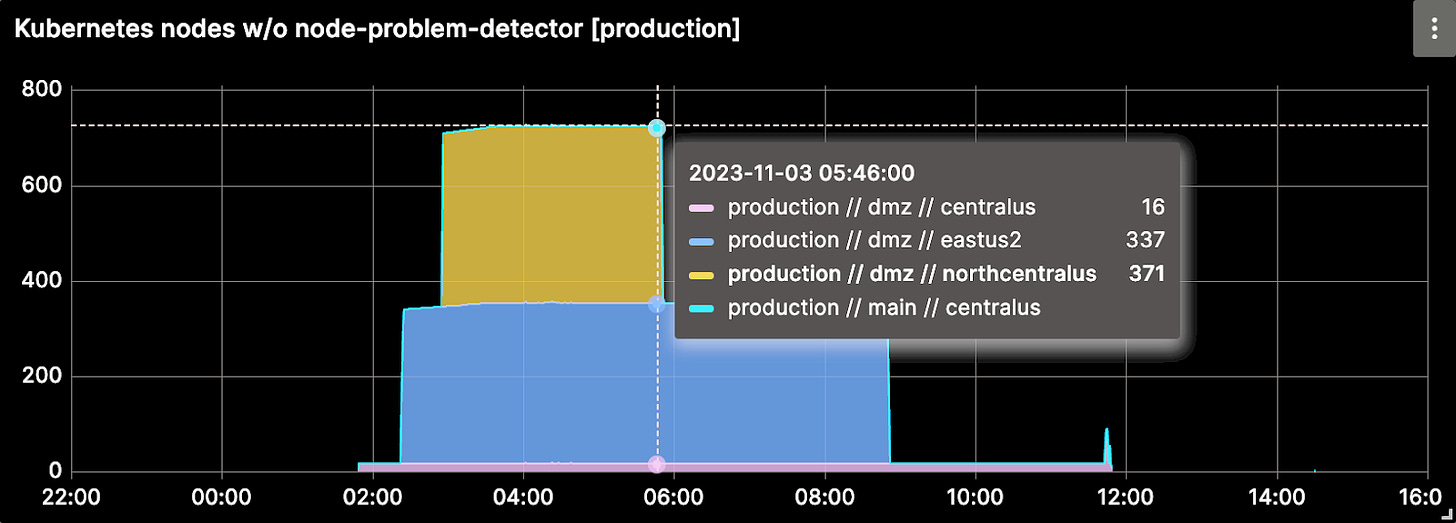

Addressing node-problem-detector Missing on Nodes

AKS runs node-problem-detector (NPD) to monitor node health and flag for removal during malfunction. It runs 10 checks every 30 seconds and injects the output into node conditions. We integrated these conditions into our observability stack. During a workload failure investigation, we noticed a node had only 4 status conditions instead of the usual 14 (10 from NPD and 4 from kubelet). This led us to discover NPD wasn’t running on the node. The workload failed because Container Runtime Interface (CRI) malfunctioned on the node preventing kubelet from verifying workload status.

We implemented a self-healing detector that flags nodes where NPD isn’t running. Further analysis revealed 25% of our nodes had this issue. Automatically terminating these nodes was deemed too risky. Instead, we rolled back the node OS on all of our nodes to a previously working version and escalated the issue to the cloud provider (see issue #3988). This was later attributed to an upstream CVE that was fixed. We also set up automated alerts for nodes without NPD to prevent future issues.

Mitigating ImagePullBackOff Errors for Large Container Images

We faced a surge in ImagePullBackOff errors for workloads with large container images (7-10GB). The kubelet error messages (example below) were unhelpful, and workloads failed to start for hours. Manual eviction sometimes helped after multiple retries. An unrelated experiment benchmarking write speeds on Azure Managed OS disk and Ephemeral OS disk, led us to identify that the issues occurred exclusively on nodes with Managed OS disks.

Oct 31 11:57:43 aks-nodepool0392-17898922-vmss0000LX kubelet[2874]: E1031 11:57:43.120279 2874 remote_image.go:242] "PullImage from image service failed" err="rpc error: code = Canceled desc = failed to pull and unpack image \"cssacrprod.azurecr.io/chronorepo-companion-cron:efdc4a316aebcc878c38483b09bb939524dbd94a\": failed to commit snapshot extract-332345855-2JgL sha256:d2bd2b7dd52900b17c2e8d2f50d94273892a45d96a760f078aeb58bc54fbc160: context canceled" image="cssacrprod.azurecr.io/chronorepo-companion-cron:efdc4a316aebcc878c38483b09bb939524dbd94a"We implemented a self-healing detector that flags nodes with ImagePullBackOff errors by parsing kubelet logs. Currently, we lack an automatic fixer. Instead, we emit a custom warning event for each affected pod. Affected workloads can either retry, or if the issue persists, set a node affinity for label ephemeral-storage = true. All nodes in our platform with Ephemeral OS disks have this label.

Conclusion

Building out a self-healing solution for Kubernetes has allowed us to enhance the reliability of our Kubernetes platform without burdening ourselves with operational and support toil. Automation proved to be the right principle for us to scale to 100s of clusters.

So, what’s next? We are constantly adding new detectors and fixers to our self-healing framework. Low level networking, noisy neighbor problems, CPU core use optimizations are few examples of areas we are actively investigating how to automatically detect and rectify problems. Furthermore, we plan on extending the framework beyond platform deficiencies to application deficiencies. We are confident the same mechanics of self-healing are widely applicable. Self-healing is the only answer to having a platform’s maintenance costs scale sublinearly with business growth. So we’re serious about investing in it further.