Data-Driven Automated Marketing for Restaurants

How Otter Marketing helps restaurants to increase revenue

Written by Xiangyu Sun and Ye Tian, members of the engineering teams that work on Otter Marketing.

Running promotions and ads on Online Ordering Platforms has become an effective marketing tool to increase exposure and drive sales for restaurants. However, making informed decisions about which promotions to deploy, customizing them for different times and platforms, and assessing their performance remains challenging. Relying solely on manual processes for campaign management can be not only labor-intensive but also suboptimal.

We've developed an automated marketing system inside Otter, the all-in-one restaurant operating system. It has helped Otter customers boost their online marketing with an average revenue uplift of 12%. In this blog post, we'll explore the key factors and design decisions that contributed to this success.

Prediction and optimization

At first glance, manually creating a static timetable for marketing campaigns may seem straightforward, but this approach becomes impractical due to escalating complexity. With numerous configurations targeting different audiences, discount levels, and so on, the combinations can easily exceed hundreds. When factoring in variables such as days, variations across different Online Ordering Platforms, and multiple store locations under management, the number of choices multiplies to tens of thousands.

We address this complexity by forecasting the potential outcomes for each option, allowing us to compare alternatives and identify which performs better. Then, we employ linear programming to search for the optimal combination of options, adhering to global constraints like the marketing budget.

Prediction

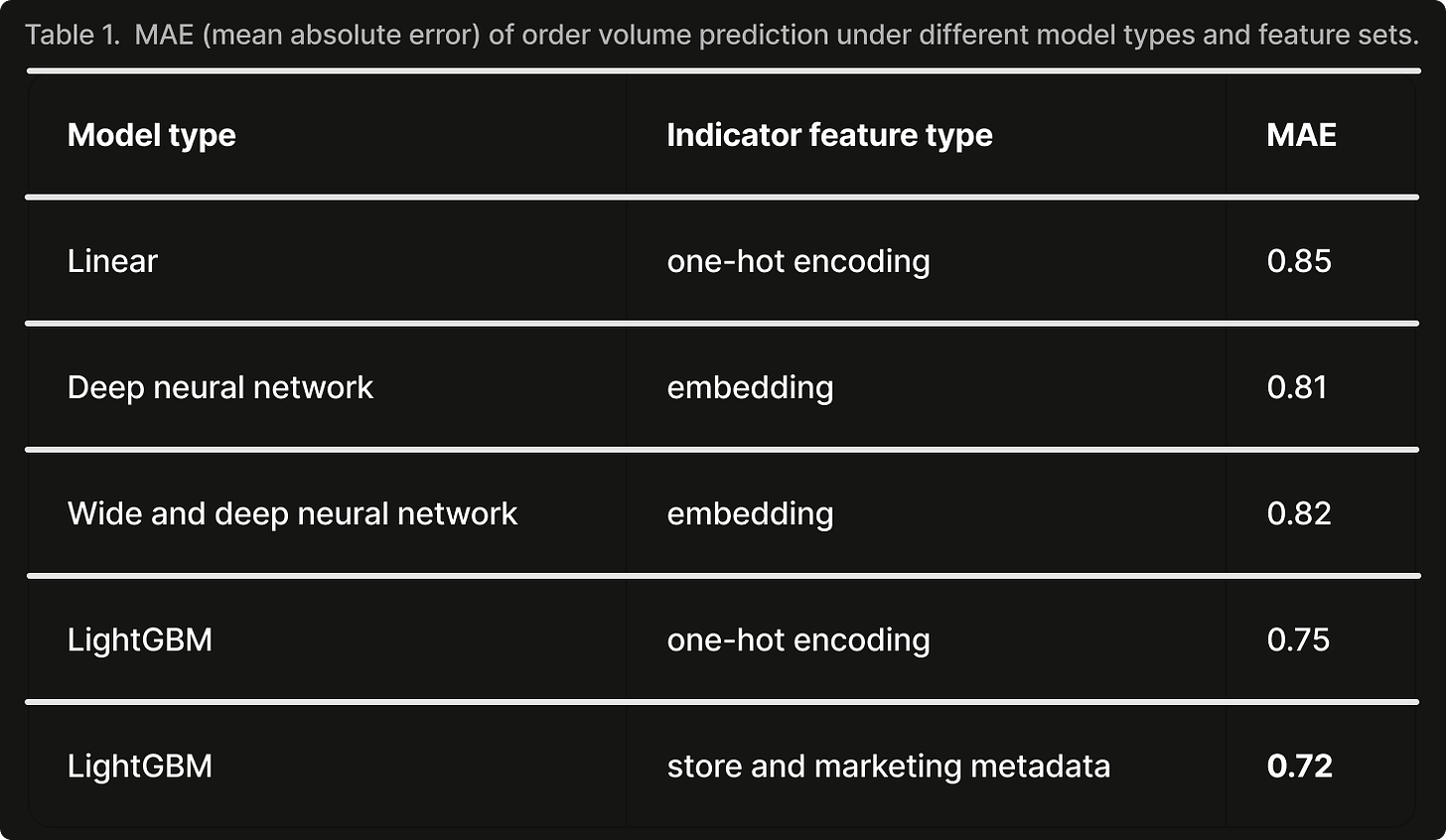

Historical data offers insights into how business outcomes fluctuate with the timing of marketing campaigns, as well as the impact of geolocation and restaurant type. Using this data, we constructed a suite of time-series regression models to predict key business indicators, such as revenue, order volume, profit, and marketing spend. We experimented with various modeling techniques, ranging from linear models to gradient-boosted trees and neural networks. Ultimately, we chose gradient-boosted trees implemented through LightGBM for its superior performance (see Table 1) and simplicity.

More importantly than the type of model, we discovered that feature engineering warranted greater effort to improve training metrics. As we aimed to capture the nuances between different stores and promotion types, one challenge was encoding this information within the feature set. Our initial method was to use one-hot encoding, assigning unique IDs to each restaurant and promotion type. However, this approach created high-dimensional sparse feature vectors that not only inflated the model size but also failed to capture semantic meanings. For instance, it did not readily reflect when two stores were in close proximity and served the same cuisine, or that promotions like “Spend $20, save $5 for all” only differed from “Spend $20, save $5 for new customers” in their target audience.

A common approach to address this high dimensional feature space is to project them into low-dimensional dense embedding spaces, allowing the system to reflect relative semantic closeness. However, this technique is generally more compatible with neural networks and demands a considerably larger amount of data and fine-tuning. Therefore, we opted to derive the low-dimensional space directly from the semantic meanings. Rather than employing restaurant IDs, we represented each restaurant by the demographic information of its location and operational characteristics, such as ratings and cuisine type. Likewise, instead of using promotion type IDs, we utilized marketing metadata including the intended audience, minimum spending threshold, maximum discount amount, and ad bidding values. This method yielded a much shorter and denser feature vector with significantly improved training metrics as shown in Table 1.

Optimization

In the absence of constraints, making marketing decisions can be straightforward—simply choose the option that maximizes daily revenue, for example. However, restaurateurs often face more granular requirements, such as running promotions only three days a week or keeping marketing spend below a certain threshold within a given period. When multiple Online Ordering Platforms or stores under management are subject to a shared pool of constraints, the combinatorial possibilities skyrocket, rendering the greedy approach ineffective.

Under these constraints, the challenge transforms into a global optimization problem: determining where, when, and how much of the marketing budget to allocate in order to maximize the aggregate goal across platforms and stores while adhering to the constraints. We formulated this as a mixed-integer programming problem and employed OR-Tools as the solver to identify the optimal combinations.

Putting together

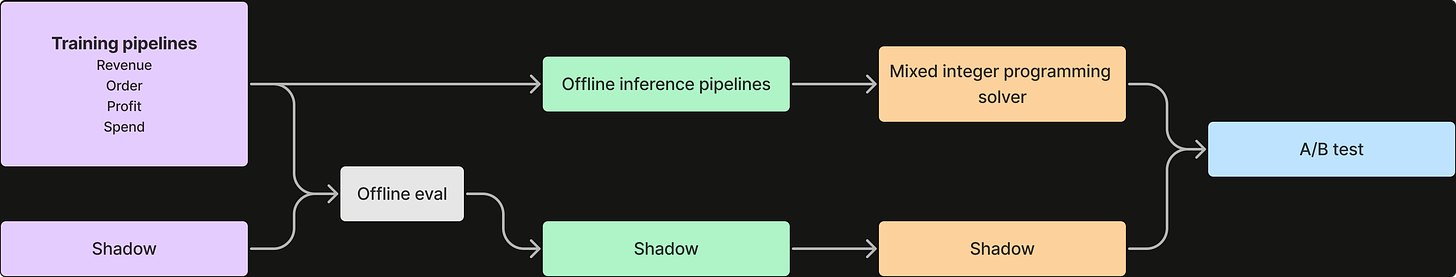

We deployed cron workflows orchestrated by Argo to execute training jobs concurrently, followed by inference and the linear programming solver. All pipelines are updated daily to accommodate new observations that come in every day and to reflect updated constraints.

To enable experimentation, we implemented a shadow system, allowing us to modify models, post-process results, update linear programming solvers, and log and compare outcomes with the production system. Any changes to the models are subjected to offline evaluation to ensure they do not compromise training metrics. Before releasing model updates and alterations to the rest of the pipeline, they must undergo online A/B testing to confirm that the changes yield beneficial and statistically significant results. In the following section, we will detail the setups for online testing.

Measurement and experimentation

The shadow system acts as a testing ground where we can explore new features, refine models, and evolve our optimization algorithms. Once changes are primed for trial, we allocate a subset of stores to operate with the shadow system and compare their performance with a similar group of stores running on the production system.

Timeline A/B

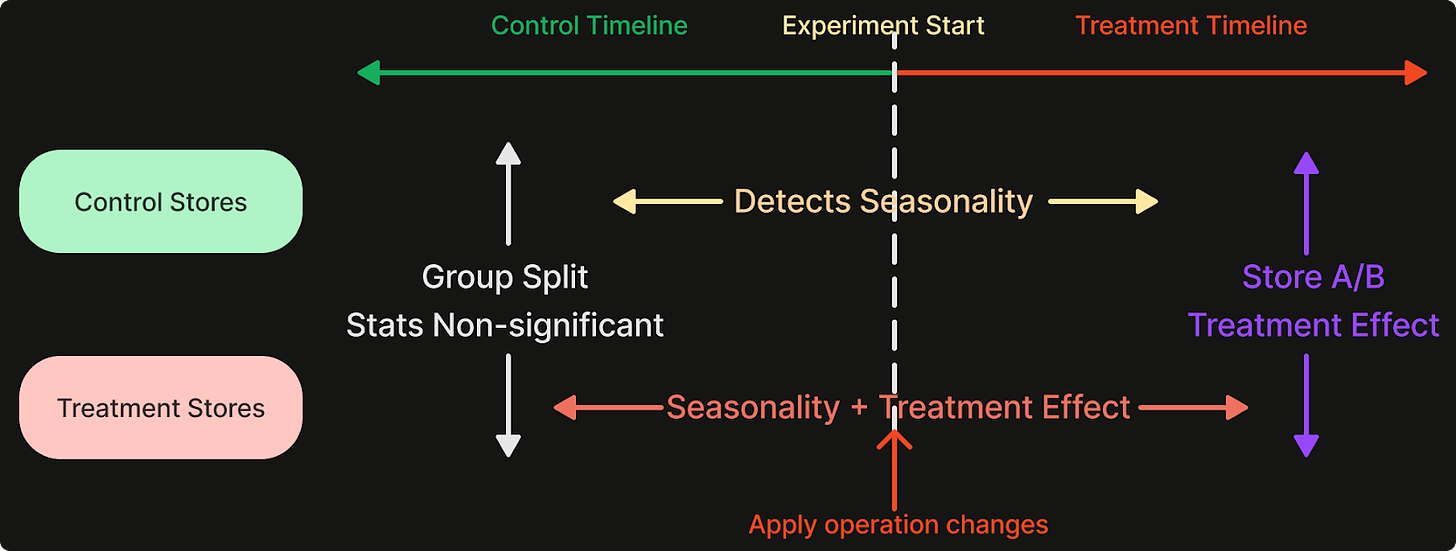

The Timeline A/B experiment is conducted using two comparably profiled groups of stores over two consecutive, equal-length time frames: the control period and the treatment period. During the control period, both the control and treatment groups operate under identical configurations. Then, at the beginning of the treatment period, we transition the treatment group to the shadow system.

To eliminate any pre-existing biases in the groups, the control and treatment groups must not exhibit any statistically significant differences across any of the test dimensions such as daily average revenue. Our initial step uses high-level filtering criteria to select candidates for the experiment. Then, we take data from the period immediately preceding the start of the experiment, bucketize it based on a primary dimension like revenue, attempt a random split within each bucket, and combine the subdivided buckets into control and treatment groups. Next, we conduct t-tests across all testing dimensions. A split is deemed successful if it shows no significance in any of the dimensions. If such a split proves challenging to achieve, we would then revisit and adjust the selection criteria for candidates.

The Timeline A/B experiment design enables store-level comparisons and difference-in-differences analyses. Using these methods, we can determine if changes implemented in the shadow system result in statistically significant improvements by controlling for temporal variations.

A/B testing results should also be congruent with human judgment for interpretability. For instance, we conducted a test to compare system responses under different objectives: maximizing order volumes versus maximizing profit, in scenarios without budget constraints. The outcomes were insightful. When the objective was to increase order volumes, the system suggested highly aggressive promotions, which entailed steep discounts with minimal qualifications. In contrast, when the goal was to maximize profits, the system recommended more conservative strategies, like offering free delivery exclusively to new customers or modest discounts with higher spending thresholds.

Switchback

In situations where the population is insufficient for timeline A/B splitting, or when the test is better conducted within the same cohort (like budget optimization only applies to the same organization), we utilize switchback testing. This method alternates between control and treatment settings at fixed intervals on the same cohort. Companies like DoorDash have employed this technique to run experiments in scenarios where network effects might influence the outcome, where control and treatment groups are not independent and can impact each other. Because the experiment involves a single cohort, we can pair the control and treatment intervals and employ paired testing methods to enhance statistical power.

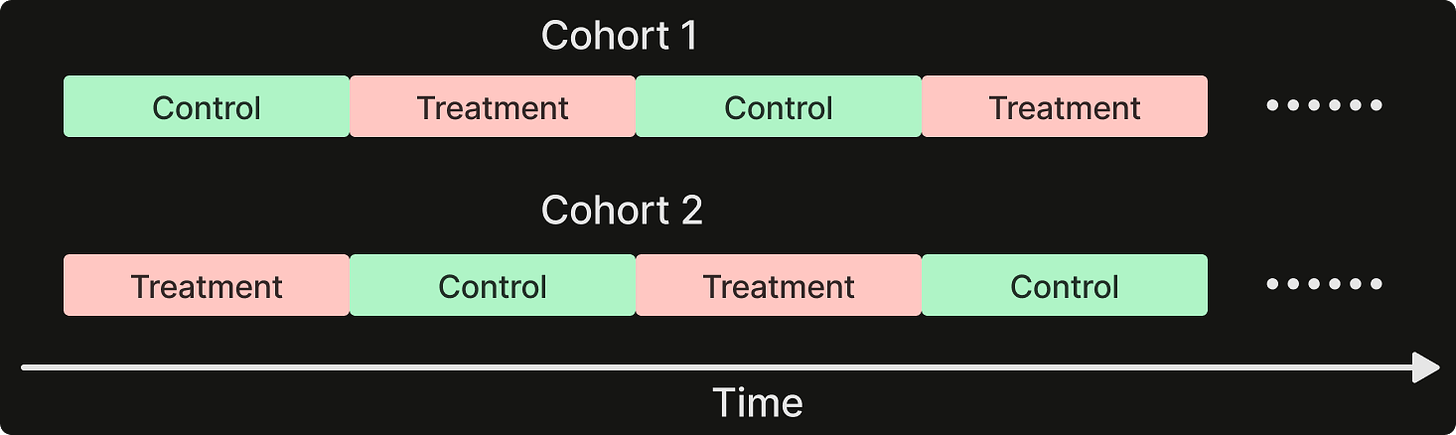

Switchback testing avoids the issue of uneven cohort splitting, but it does not completely eliminate the potential impact of time differences between control and treatment periods. To mitigate the risk of results being affected by coincidental timing, one strategy is to extend the duration of the experiments. Another approach is to run concurrent experiments on two cohorts with reversed control/treatment schedules and then pool the data for analysis.

We carried out an experiment to evaluate the effectiveness of global optimization across a large group of stores with a shared budget constraint. The control group utilized a greedy approach, optimizing decisions for each individual store, whereas the treatment group applied the global optimization method discussed earlier. Under this holistic optimization strategy, not every store receives the decision that would maximize its individual outcome, but it prevents marketing pauses due to overspending. This approach is particularly effective when budget constraints are tight. In our experiment, where the total discount could not exceed 30% of revenue, we observed a statistically significant increase of 7% in total order volume for the treatment group compared to the control group.

Continuous monitoring

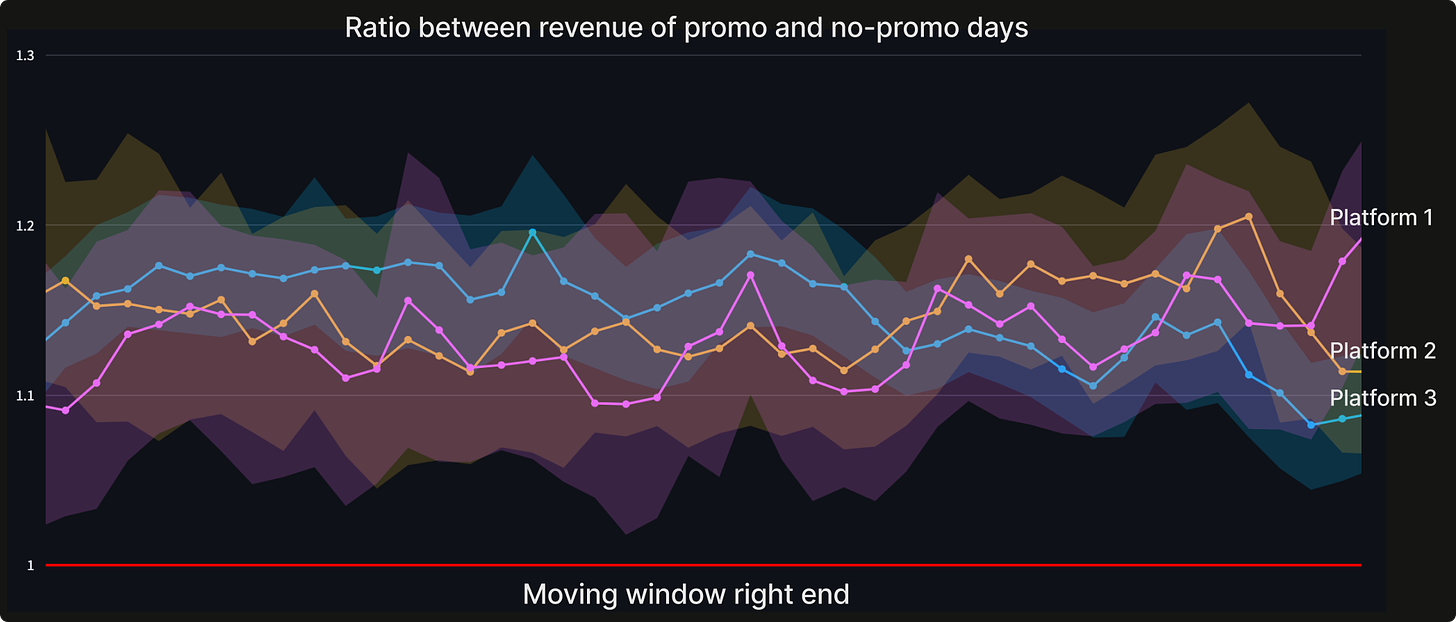

Beyond online testing, which is designed for controlled experiments to validate system improvements, we also establish continuous monitoring of the production system to gauge the efficacy of marketing decisions. A key metric we monitor is the "incremental gain attributable to marketing," which we calculate by comparing scenarios with and without marketing at an aggregate level over a rolling window. Within a rolling window, we calculate the ratio of revenue between days with promotions and days without promotions. We expect that revenue on promotional days will be higher than on non-promotional days, hence the ratio should remain above 1.

If the benefits of marketing-led scenarios begin to diminish relative to non-marketed ones, we initiate a human-led investigation to identify potential system bugs or sudden shifts in market conditions. Fortunately, our experience thus far has demonstrated a consistent uplift from marketing efforts between 10% to 20%.

Conclusion

In this post, we discussed the development of Otter Marketing, a tool designed to help restaurant owners navigate online marketing across various platforms to maximize their budget's efficacy. Utilizing predictive models and optimization solvers, the system determines the most effective action from tens of thousands of possibilities each day. With our online testing and monitoring frameworks, we ensure that the benefits of marketing are tangible and significant, guaranteeing that our customers' promotional dollars are effectively utilized.